The Lawyhers Behind MLK’s Legal Strategy — and Why Their Legacy Matters Now

- Hadiyah Cummings

- Jan 19

- 5 min read

I usually spend Martin Luther King Jr. Day rereading Letter from Birmingham Jail. It is a ritual of sorts. That letter re-sparks something radical in me — the part of myself that believes deeply in moral urgency, collective responsibility, and the possibility of a world that is fundamentally more just than the one we inhabit. It reminds me that Dr. King was not the sanitized figure we are often taught, but a strategist who understood that discomfort was often the price of progress.

But if I am honest, that radicalism has been tempered by the day-to-day realities of being a civil rights lawyer. By deadlines, institutional constraints, funding limits, and the slow grind of systems that resist change. Over time, the ability to dream freely — to imagine a bigger and better world — can feel dulled.

This year, instead of returning to the familiar words of Birmingham Jail, I chose to read something different. I spent the day learning about three women lawyers whose work powered Dr. King’s legal strategy. Women whose names are rarely centered, but whose labor helped make the civil rights movement enforceable, durable, and real.

As civil rights lawyers, we stand on the shoulders of giants. Reading about Constance Baker Motley, Marian Wright Edelman, and Pauli Murray reminded me how deep and wide the struggle for justice has always been — not just in the headlines, but in the grind of legal strategy, courtrooms, and community advocacy.

These women didn’t merely assist a movement. They shaped its legal backbone at moments when the country was being pushed — kicking and screaming — toward basic recognition of human dignity.

Constance Baker Motley was a force of nature in the courtroom. She was the first woman lawyer at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and represented Dr. King during the Birmingham Campaign in 1963 — the mass protest effort that brought national scrutiny to segregation and violent repression in the South. Her legal work protected demonstrators, challenged segregation in court, and helped translate civil disobedience into enforceable legal rights. She later became the first Black woman federal judge, shaping civil rights law from the courtroom to the bench.

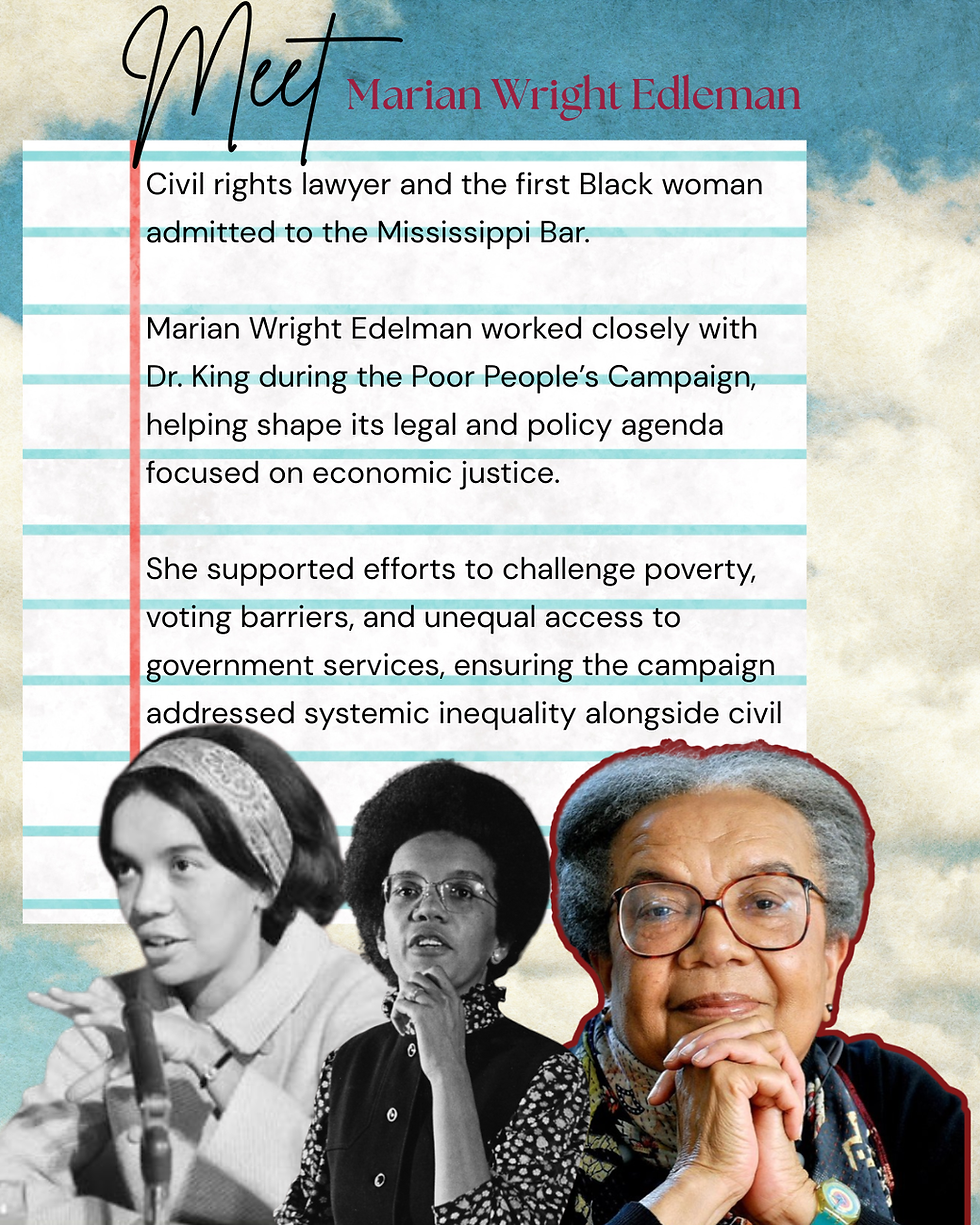

Marian Wright Edelman broke barriers as the first Black woman admitted to the Mississippi Bar and worked closely with Dr. King during the Poor People’s Campaign. She helped shape its legal and policy agenda, making clear that civil rights was not only about racial equality, but about confronting poverty, voting barriers, and systemic exclusion. She went on to found the Children’s Defense Fund, where she continues that work today, advancing economic justice and advocating for children and families nationwide.

Pauli Murray gave the movement its legal imagination. As a lawyer and legal scholar, they developed constitutional frameworks that influenced NAACP litigation strategy and later formed the basis for dismantling both racial segregation and sex discrimination. Their work did not always make the headlines, but it made the law. Much of the legal architecture the movement relied on bore their intellectual imprint.

Their stories are a reminder that we do not wake up on the “right side of history.” Rights are made — deliberately, often painfully — through organizing, legal strategy, and sustained pressure. We did not wake up one day with the Civil Rights Act of 1964. We did not stumble into school desegregation, voting protections, or anti-discrimination law. Those victories were built by community organizers and lawyers alike, working in tandem, often at great personal risk.

Living in the Shadow of Their Work — and Today’s Backlash

That reflection feels especially urgent now.

We are living in a moment when the institutions once tasked with enforcing civil rights are being weakened or repurposed. The U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division, created during the civil rights movement to enforce federal civil rights laws, has seen an exodus of attorneys under the current administration — with roughly 250 attorneys, or about 70 percent of the division’s staff, leaving or planning to leave amid mission shifts and restructurings.

Multiple senior prosecutors have recently resigned rather than participate in decisions that exclude the Civil Rights Division from key investigations, including the response to the fatal shooting of a Minneapolis woman by a federal immigration officer.

At the same time, we are witnessing aggressive federal actions that place communities under siege. In Minnesota and elsewhere, armed and masked federal immigration agents have conducted raids that local leaders and advocates describe as terrorizing neighborhoods, separating families, and operating with little transparency or accountability. For many communities, this feels less like law enforcement and more like state-sanctioned fear.

Recent reporting has also underscored a troubling reality: over the last several decades, Americans have lost more civil rights protections than they have gained. Gains once thought settled are now contested, narrowed, or quietly abandoned. This is not a coincidence. It is the predictable result of disinvestment in enforcement and a political climate that treats civil rights as expendable.

This is not the world those women lawyers envisioned when they filed briefs, advised organizers, and stood in hostile courtrooms insisting that the Constitution meant what it said.

What It Means to Be a Young Civil Rights Lawyer Today

As a young civil rights lawyer, reading their journeys was both humbling and galvanizing.

Their work was not glamorous in the moment. It was meticulous, strategic, and often invisible. They did not wait for permission to lead, nor did they rely on federal institutions alone to validate the justice of their cause. They built parallel paths — through courts, communities, and policy — understanding that progress requires pressure from every direction.

That lesson feels critical today.

If federal enforcement is unreliable, then the work must become more local, more creative, and more deeply rooted in community. It requires us to think beyond traditional pathways and ask harder questions about how we use the law in service of real people. It means investing in legal education, empowering communities to know and assert their rights, and building coalitions that do not collapse when one institution fails.

Leadership, in this moment, is not about visibility or accolades. It is about responsibility.

About choosing to stay in the work even when progress feels slow, and when the outcomes are uncertain.

Remembering the Full Story

And perhaps most importantly, we must remember that movements are never the work of a single figure. While some names are etched into history books, countless others labored behind the scenes — drafting, organizing, litigating, and imagining a future that did not yet exist.

The lawyers behind MLK’s legal strategy remind us that civil rights victories are collective achievements. They are built by people who refused to accept injustice as inevitable and who understood that law, when wielded strategically and ethically, can be a powerful tool for change.

That is the inheritance we carry. And that is the work we are called to continue — with courage and a willingness to dream again, even when the world makes that feel difficult.

Comments